Sound is known to spread. Like honey, it has a particular capacity for escaping its containers. It makes a mess. It leaves nothing untouched. Despite touching everything, it is difficult to apprehend. Its immateriality slips through conceptual grasping and linguistic parameters. The difficulty with which one describes what sound is can only be matched by the ease with which sound produces meaning. Inherently evocative, its medium is potent with potential to move and expand. This is Dickinson’s worry when she asks, “is it unconveyed, like melody or witchcraft?”

I’d like to begin with the text by Deborah A. Miranda because it sets the stage for our seminars, posing the question, “how is it that one can learn?” We can understand the process that allows for the acquisition of discrete forms of knowledge (that which might be useful at trivia night), but the process that allows for the conveyance of the un-conveyable is more difficult to discern. How might we produce environments that coax out these knowings if they cannot be handed off like an object or a word? How do we know that we know these knowings if they are not granted the privilege of identification, of a name?

Miranda offers the evocative potential of sound as a framework for understanding the unfolding of this particular form of learning. “What if these knowledges, always here, can be evoked from one being to another—in a moment of resonance,” she asks. This stands in direct opposition to the transactional, advocating for a form of learning that brings forth the already present and disrupts the possibility for knowledge’s commodity form. This learning is understood to be embodied by definition; one feels the moment in which something external (a text, a melody, an image, a rhythm) results in a rise or an activation. This is an individual experience.

A religious person might mistake the particularity of this form of learning for the acquisition of something universal, something preexisting that is “tapped-into.” It is this that Vivian Darroch-Lozowski appears to describe when she is confronted by her privilege at the moment of associating the beauty of a frozen landscape with tears of the marginalized. She argues that this association, between the image of the ice crystal and the tears of suffering, comes as a result of the electromagnetic quality of the word as it is enacted by the brain. These frequencies, in Darroch-Lozowski’s framework, are ontologically prior to the words themselves and allow for an “interbeing…where discoveries form a re-hearing of words with which we are all familiar.” Thus, the individual evocations described in “Like Melody or Witchcraft” are here reconfigured as moments of access to universal truths awaiting discovery.

The resulting politics of this framework are one that treats words as a scarce, finite resource. Derroch-Lozowski goes on to describe “the ultimate task” of words as the capacity to “shift perceptions and understandings away from usual habits of thought and usual frameworks of knowing.” Is it not words that have the capacity to shift understandings, it is their mischievous use. We do not need more words, we need more rubbing, frictions that produces resonances. This humming is dialectical by nature, a third thing arising from the heat of conflict between an external two. Darroch-Lozowski knows this, perhaps, but attributes this third to a universal wellspring as opposed to an individual evocation of her mind. I think here of the surrealist, Max Ernst who followed the lead of his unconscious to coax images from found textures in his frottages (rubbings).

If we are to depart from Darroch-Lozowski’s electromagnetic universalism and read the works of fiction with Miranda’s resonances in mind, there emerges a continued relationship between the sonic and the unconscious or imaginary. Clarice Lispector’s “The Triumph” begins with a sensory double, a clock lets out a “loud, sonorous peal” quickly followed by a “bright stain of sunlight,” what David Bowie might describe as “sound and vision.” Before our character, Luísa opens her eyes, we begin to understand her world through what she hears. A crunching outside yields the picture of a “child running out on the road,” a silence yields a line of questioning that provides us with what a morning might typically sound like. In the state between dreaming and waking, sounds naturally build out images as if seeing is always done with the ears.

It is the moment that Luísa opens her eyes that reality comes crashing in. “It’s true then…,” she admits after witnessing the empty bed across from her own. Despite the frankness of her vision, she adds that “she could still hear his words.” This is an artifact of audio’s capacity for invoking the imagination; the line between perceived sound and remembered/hallucinated sound can be difficult to parse out [^1]. Audio’s propensity for misalignment with the present allows for fabricated auditory experiences to avoid uncanniness. We are used to listening to recorded music as we walk the streets without expecting that the music is a sensation of our environment. We understand that a podcast is a palimpsest of durations, to use Bergson’s term from Matter and Memory. We do not expect audio to tell us something about where we are, but it may if we’d like it to.[^2]

The capacity for audio to act at a distance is exemplified in Heinrich Böll’s “Murke’s Collected Silences,” where Murke is tasked with replacing each instance of the word “God” in an audio recording with the phrase, “that higher Being Whom we revere.” Beyond the obvious fabrication of the radio show, the environment of the office building is rigged such that sound may impose authority without the presence of the authoritative body.

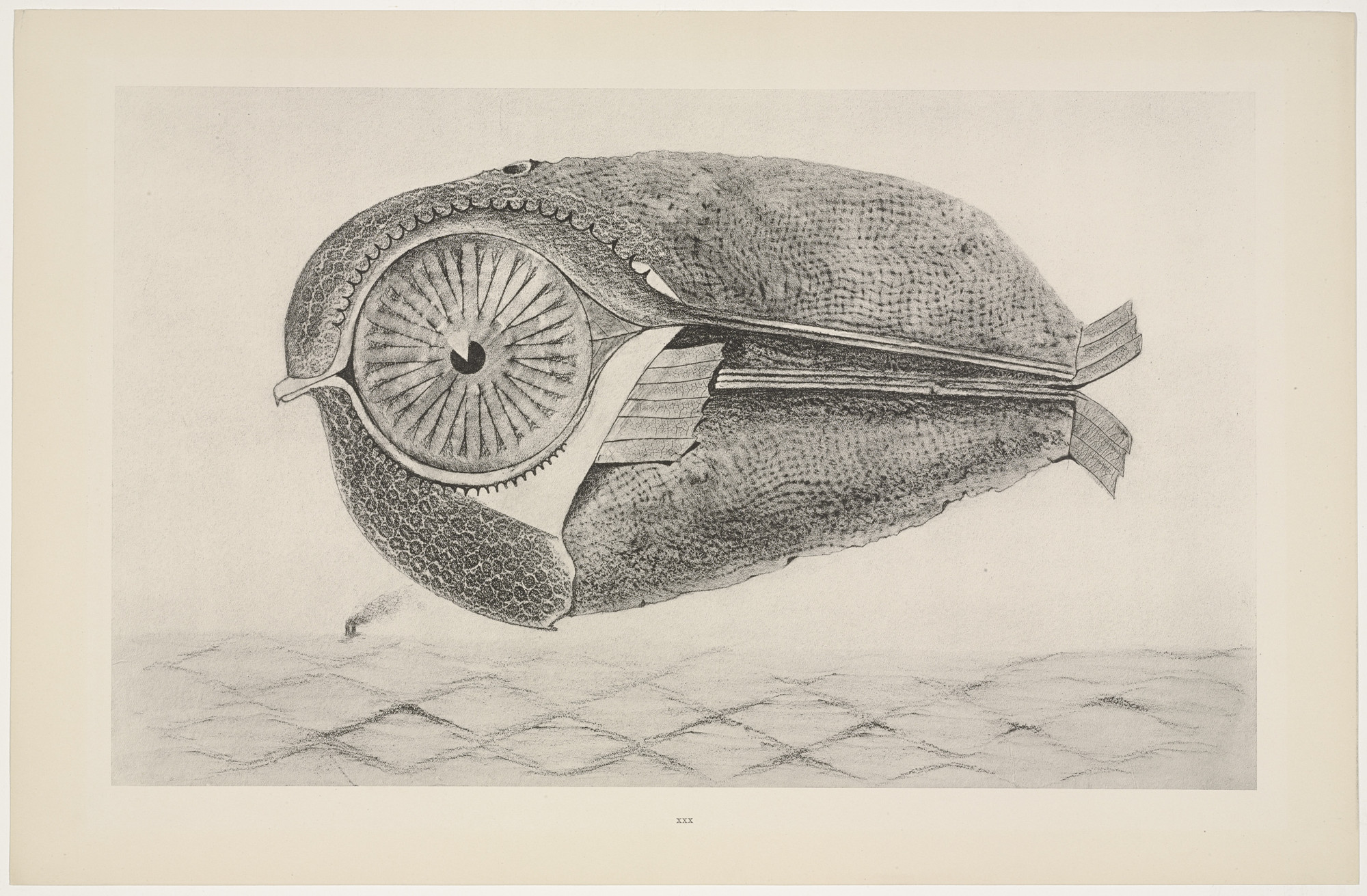

While editing the radio show, Murke and the audio technician remain in a sonically isolated room connected to the recording room by a glass window. Murke can see Bur-Malottke speaking into the microphone but cannot hear him. Inversely, Bur-Malottke cannot see Murke, but can hear him when he speaks through the microphone. Through the disembodiment of his voice, Murke is able to access a form of power over the famous, Bur-Malottke that renders him “helpless.[^3]” Sitting in the editing room, Murke describes BM as “soundless, like a fat, handsome fish.” May it be postulated that the sonic distance of the two characters allows for the erosion of professional niceties, giving way to a sadistic voyeur fantasy?

Later in the story, we discover BM’s desire to change each instance of the word “God” in his entire audio archive so as to align the utterances of his past self with his present thinking and belief. He says, “one day I shall… die…and I cannot bear the thought that after my death, tapes may be run off on which I say things I no longer believe in.” Audio’s ability to produce afterlives is one of the qualities that makes recorded audio’s evasion of the uncanny most profound. Recorded audio as a technology that allows the dead to speak introduces the illusion of the presence of the deceased or absent, perhaps conjuring memories and inducing dreaming but without the unease introduced by other forms of simulation.

While there is much to say here about audio’s capacity to revive the voices of the dead, it must be stated that it is difficult to pull this quote from its context. Taking place in postwar Germany, the population is haunted by the specters of its fascist history. The writer himself, while remaining critical of the Nazi regime, was drafted into and the army of the Third Reich. It was a time in which unearthed audio recordings that proved individuals’ complicity in the party’s war crimes could result in prison sentences and death. This might explain Bur-Malottke’s particular preoccupation with the ideological consistency of his archive.

Ultimately, the texts synthesize a number of perspectives on the process through which sound induces the imagination, opening up our thinking in such a way that our minds become capable of profound external influence. This quality of the sonic can be both liberatory in its dehabituating tendency and dangerous in its capacity to produce compliance. How may we wield the sonic to foster the former, making ourselves unfamiliar such that we become susceptible to ways of perceiving that we have lost? How may we wield it to evoke each others’ dreams?

[^1] I wonder how Bergson’s conception of “images” in Matter and Memory maps onto the perception of audio. Put simply, Bergson posits that we can never really “see,” as our vision is, by its very nature, an act of remembering. Seeing, then, can only occur through the veil of remembered “images” and is thus inherently subjective.

[^2] We may let audio help us place ourselves even when it is fabricated. This is audio’s capacity for invoking the dream.

[^3] We could, perhaps, view Murke’s omnipresent voice as the voice of the very God that Bur-Malottke is trying to erase while viewing BM’s subsequent unheard and helplessness protesting as an element of his disenfranchisement with the higher power (like an unanswered prayer).

***

Reading response written for Stolen School Week 1: Sonic Silences

-“Like Melody or Witchcraft: Empowerment Through Literature” by Deborah A. Miranda

-“Living Scores” by Oana Avasilichioai

-“Silence” and “The Triumph” by Clarice Lispector

-“Speech Sounds” by Octavia Butler

-“Murke’s Collected Silences” by Heinrich Böll